"What humiliation when any one beside me heard a flute in the far distance, while I heard nothing, or when others heard a shepherd singing, and I still heard nothing!" wrote Ludwig van Beethoven in a letter to his brothers in 1802. Despite being a musical genius, Beethoven began losing hearing in his late 20s. Some theories suggest his deafness might have been due to damage to the cochlear hair cells in his inner ear- a cause of hearing impairment in more than 90% of cases today. Loud noises, aging, medication side effects, infections and genetics can damage hair cells. Mammals, including humans, evolved to detect a wide range of sound frequencies, but this trait came at the cost of losing the ability to regenerate hair cells when damaged. Birds, however, play by different rules. They can regenerate hair cells and restore their hearing.

In all spine bearing animals, hair cells are surrounded by supporting cells that keep them healthy. In birds, when hair cells are damaged or lost, the supporting cells step in and transform into new hair cells. A recent study from the National Centre for Biological Sciences identified crucial molecular clues about how this restoration might work in Chicks. These insights could potentially address permanent deafness in humans in the future.

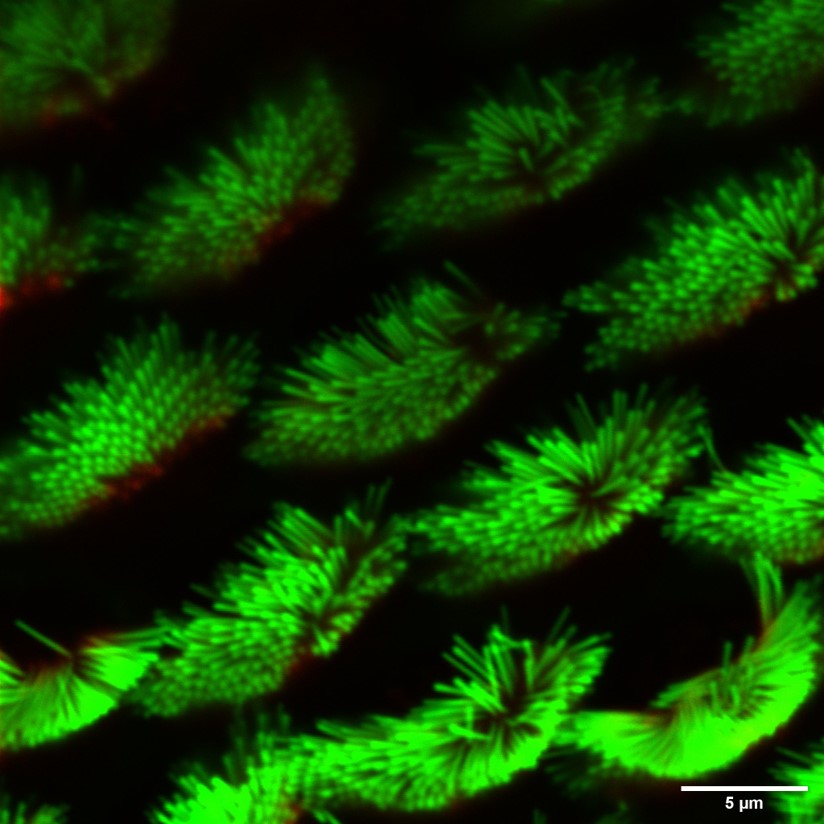

When sound reaches the inner ear, hair cells in the cochlea sense it with their tiny hair-like structures. These cells then send signals to neurons, which carry the information to the brain. Damaged hair cells cannot sense sound or communicate with the neurons, impeding sound signals to the brain —resulting in hearing loss. Both supporting cells and hair cells come from the same precursors. The research team used CRISPR technology to delete a gene called Atoh1, which drives hair cell formation, from these precursors in developing chick embryos. As expected, hair cells did not form at the usual time, but they made a comeback later. While Atoh1 is crucial for forming hair cells during early development, birds can still restore these cells later when they are damaged or lost, even without this gene.

So, how does a chick pull this off?

“The chicken auditory epithelium maintains homeostasis by sensing lost hair cells with the help of the supporting cells that surrounds them. These supporting cells recognize the loss and kickstart a restoration process. They do this either by dividing or transforming into new hair cells.” says Nishant Singh, the lead author of the study. The team used proliferation assay to support this finding.

Cell growth and development in animals is guided by molecular mechanisms – the Wnt and Notch pathways. Wnt pathway helps hair cells grow, while the Notch pathway decides if a precursor cell would become a hair cell or a supporting cell. But do they also help restore the hair cells? The team investigated how tweaking the Wnt and Notch pathways affected hair cell restoration in the Atoh1 deleted cells. They discovered that boosting the Wnt pathway as well as blocking the Notch pathway restored hair cells. However, while inhibiting Notch signaling generated new hair cells, it did not maintain the normal arrangement of supporting cells around them, since Notch is responsible for this arrangement.

“We would like to understand why, as mammals, we cannot regenerate our inner ear hair cells. Supporting cells in birds do a double duty - their normal function in homeostatic, and make sure that the ionic balance of hair cells is correct, but they also can revert into a progenitor state when the hair cells are absent. The next phase of our study will focus on understanding why mammalian supporting cells are locked into a single cell fate and exploring ways to restore inner ear hair cells in mammals.” says Dr. Raj Ladher, the principal investigator of the study.

0 Comments