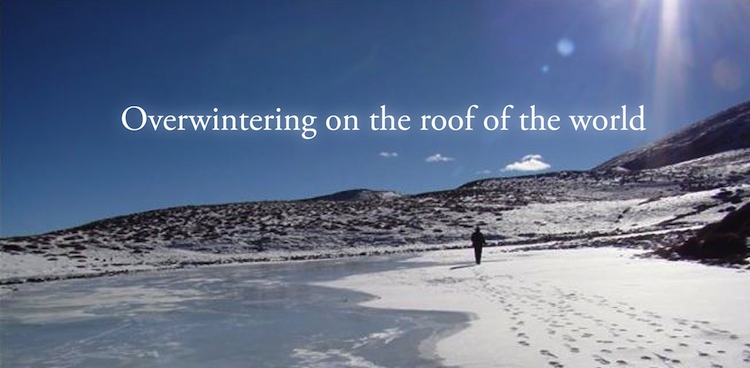

Overwintering on the roof of the world

All photographs by kind permission of Kulbhushansingh Suryawanshi. This photo edited by Shovamayee Maharana.

It hints that Kullu, as he is known to his friends, had put himself in a rather extreme situation, and sometimes in field biology this must be done. Many animals, like the Bharal (the Himalayan Blue Sheep) - the focus of Kullu's study - have carved out an ecological niche that depends on their ability to survive in an abnormally harsh environment. If field biologists want to understand how an animal can do that, they must often be willing to study it on location. Moreover, to get the maximum amount of information, they need to do so, as Kullu did, when the conditions are at their most extreme, and for the Bharal that meant the depths of the Himalayan winter, when temperatures can plunge to –35º C and below.

The M.Sc Wildlife program is not in the habit of coddling students, but none of its previous projects really came close in terms of the dangers involved. Kullu would be spending the entire winter at altitudes ranging from 3800 to 5000 metres in the remote Spiti area of Himachal Pradesh. While the project gave course director Ajith Kumar some pause, he did not believe he was dispatching Kullu on an ill-advised death-mission – for Kullu is himself a rather extreme character, and like the Bharal, admirably equipped to high-altitude survival. Kullu, although a native of the topographically sedate state of Maharashtra, has had a lifelong love of the mountains, and as well as being an accomplished rock-climber, is an advanced graduate of the famed Himalayan Mountaineering Institute. In preparing for the field work, nothing was left to chance, and no expense spared in ensuring that Kullu had the best-available extreme weather gear.

Once set up in the field, Kullu focussed on how the Bharal overcome one of the most basic but difficult challenges of a high-altitude winter: getting enough food to eat. Unlike many other Himalayan mammals that either hibernate or descend the slopes in winter, the hardy Bharal stake their claim as a real high-altitude specialist by staying put, and awake. A previous study had shown that the Bharal, almost exclusive eaters of grass in summer, switch their diet habits in winter, gradually foraging more and more amongst the shrubs and herbs. Kullu wanted to know: do the Bharal choose to do this, or is the choice made for them? Were the Bharal seeking out the shrubs and herbs, which have more nutrients than grass, as part of a special adaptive response to the winter conditions, or were they just being forced to eat them because grass was harder to find?

Kullu had a perfect opportunity to answer this question. During summer the indigenous people of the region where he did hid his work (the Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary) are allowed to graze their livestock, but to varying extents in different areas of the park. By the time winter arrives, these areas vary greatly in the amount of grass that is left for the Bharal. Kullu realised that if Bharal were actively seeking out shrubs and herbs in winter, they would, in the less grazed areas, largely ignore the readily available grass. But they did not. Kullu and his team, taking patient note despite the fierce cold and marauding Snow Leopards, found that Bharal ignored the shrubs and herbs, and in fact sought out the grass, which made up about three-quarters of their intake. It was now obvious that the winter study done previously had focussed on a highly grazed area, and thus had not provided a comprehensive picture of the Bharal's habits. Bharal only eat shrubs and herbs if they have to.

Kullu's finding, while it does not point to any fascinating evolutionary adaptation on the part of the Bharal, does have important implications for their conservation. Humans are themselves extraordinarily adaptable, and the pressures that increasing population exert in lowland India extend even to the formidable Trans-Himalaya. The agro-pastoralism of the region must be managed wisely if the Bharal are to have any chance of long-term survival. A stark reminder of this was provided by another finding of Kullu's study: female Bharal that were living in the highly grazed part of the Kibber Sanctuary had drastically fewer young than their counterparts with easy access to grass, the number of yearlings being reduced by 70%.Kullu's deep interest in the Trans-Himalaya has continued in his research work at the Nature Conservation Foundation where he is studying the conflict between humans and the large carnivores of the region, the Snow Leopard and the Tibetan Wolf. In one of his typically epic surveys, just to get to the area of interest, Kullu and his team had to ride in, nomad-style, on horseback, across 150km of the bleak plateau. It is a fascinating story, and well told by Kullu himself on his richly illustrated blog, rockstallion. Check it out to get a glimpse of the inspiration and commitment that drives this exceptional conservation biologist.

Kullu, on the banks of the Tso Moriri, Himachal Pradesh. En route to a survey of Snow Leopard numbers.

Comments

A few notes about Kullu, from

Just a couple of weeks after

One of the things I find

Post new comment