In the animal kingdom, social hierarchies are everywhere - from hornets to hyenas to humans. Being at the top often comes with perks: better access to food, mates, and a territory. But could it also offer protection from life’s psychological blows?

A recent study from NCBS, in collaboration with the University of Edinburgh looked at rat communities to explore how social status of individual rats affects their vulnerability to stress. The study shows that those lower in rank become more vulnerable to stress, both in behaviour and in their brain biology - providing new insights into how social experiences shape mental health.

Scientists study rats because they share biological similarities with humans, making them a reliable model for studying everything from diseases to brain function. Like humans, rats live in social hierarchies. This made them ideal for studying how an individual’s position within a social group can shape their response to stress.

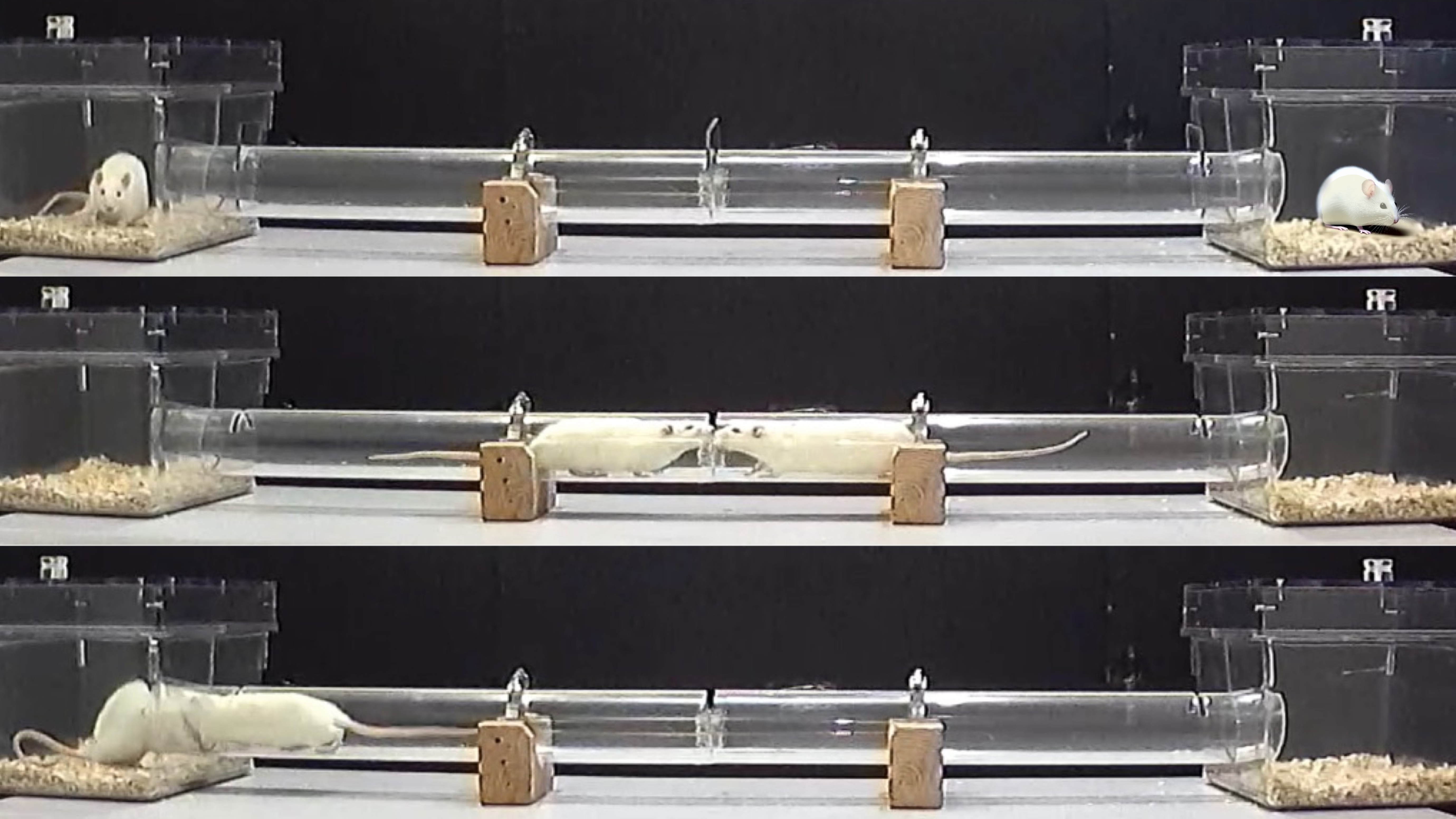

“Many factors shape how someone responds to stress - not just their genes or brain chemistry, but also their relationships and where they stand in a social group,” says Dr. Durga Srinivasan, the lead author of the study. Durga and team identified dominant and subordinate rats using a simple behavioural test called the “tube test.” In this setup, two rats face off in a narrow tube. The one that pushes the other out is deemed dominant. After several rounds of these contests, each rat’s social rank became clear.

Next, the rats were exposed to a stressful experience: being restrained in a plastic conical bag for two hours. “It’s a standard way to induce stress in lab animals - much like the discomfort we’d feel in a tight, inescapable space,” says Durga.

The team then revisited the tube test to see if stress had altered the rats' social behaviour. They ran two separate contests. In one, stressed rats faced against familiar cage-mates they had already established a social rank. In the other, a different group of stressed rats faced against unfamiliar-unstressed rats from other cages, whose social rank they didn’t know.

When paired again with their cage-mates, the social order remained unchanged. Dominant rats continued to win; subordinate rats backed down. However, the results took an interesting turn when the rats were faced with unfamiliar opponents. The researchers had a simple expectation: stress should tip the scales. A stressed rat - no matter its rank - would lose to an unstressed one. But the results told a different story. Dominant rats proved surprisingly resilient. Even when stressed, they often held their ground against unstressed rivals. Subordinate rats, however, didn’t stand a chance. Once stressed, they lost even to other subordinates who weren’t stressed.

The most surprising results came from unstressed subordinate rats. In unfamiliar matchups, they sometimes stood their ground and even won. This suggests that low social rank alone doesn’t make an animal vulnerable - it’s stress that tips the balance.

“It’s not just being at the bottom that makes you vulnerable,” says Durga. “It’s how you respond when that low rank meets a stressful experience” she added.

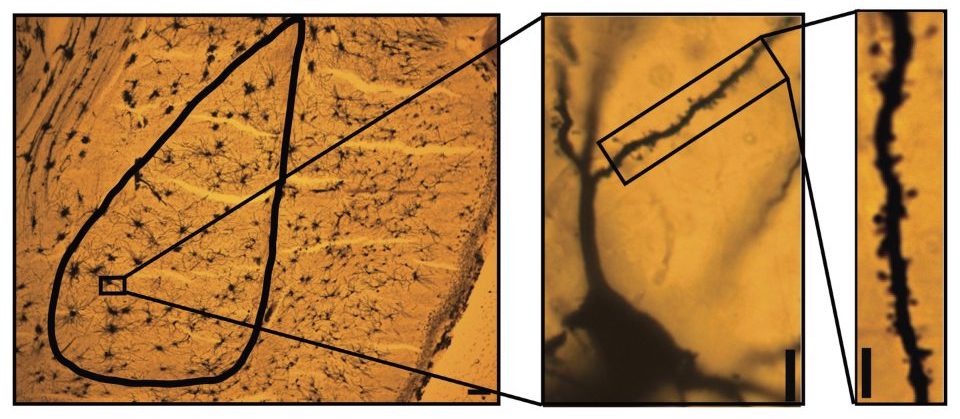

To find out if this behavioural shift had a biological basis, the researchers looked at the rats’ brains - specifically the amygdala, a region involved in fear and anxiety. They found that stressed subordinate rats had more dendritic spines - tiny, branch-like structures on neurons that help transmit signals. “An increase in these spines might reflect heightened emotional reactivity or sensitivity to stress,” says Durga. Stressed dominant rats, however, showed no changes in brain biology and no signs of anxiety-like behaviour.

Representative image showing dendritic spines in neurons from the amygdala.

“This study reminds us that vulnerability to stress is not purely biological - our place in the social world matters too,” says Prof. Sumantra Chattarji, the principal investigator of the study. “Future work could explore whether these brain changes are reversible. How effective a therapy is may depend on an individual’s social status and how they cope with stress. Successful therapeutic strategies may need to take these factors into account.”

Link to the study: https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2412314122

0 Comments