Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the world’s oldest and deadliest diseases, which takes a toll on over a million people every year. Traces of it even appear in Egyptian mummies. What makes this bacteria particularly dangerous is not merely its persistence, but its uncanny ability to manipulate our immune defences.

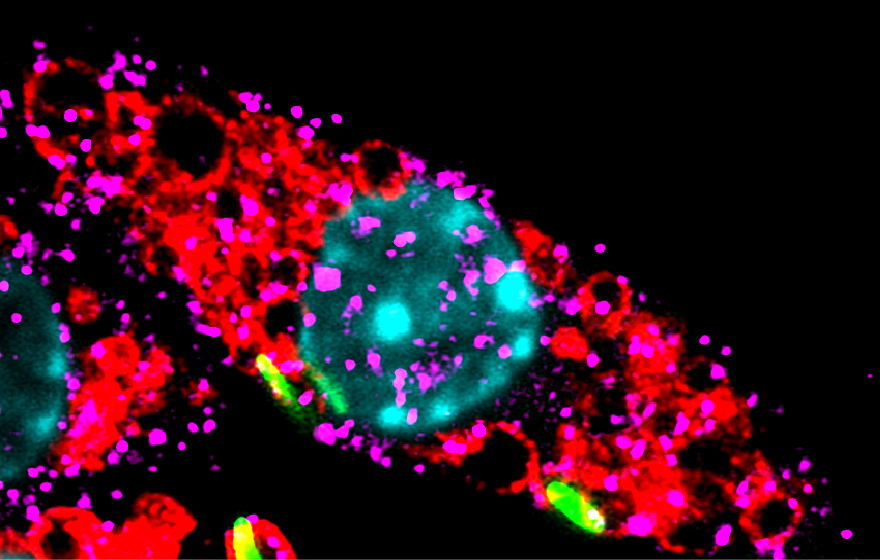

A recent study from Dr. Varadharajan Sundaramurty’s lab at NCBS reveals a new mechanism that helps Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) take over our immune system. When a microbe enters our body, specialised immune cells called macrophages engulf it by wrapping it inside a tiny bubble known as a phagosome. To destroy the invader, the phagosome must fuse with another structure called a lysosome—an organelle packed with powerful digestive enzymes. When the phagosome and lysosome merge, they form a phagolysosome–a hostile chamber that breaks down and eliminates most bacteria.

However, Mycobacterium tuberculosis has evolved clever survival strategies. One of its most effective tricks is to block the fusion of the phagosome with the lysosome. By doing so, Mtb avoids exposure to the lysosome’s destructive enzymes and safely hides within the phagosome, where it can survive.

“Blocking fusion should be enough. But recent studies noticed something puzzling. Cells infected with Mtb actually have more lysosomes than uninfected cells,” says Ibrahim Umar, the lead author of the study.

In a previous study, their team used high-resolution imaging, infection models, and genetic tools to trace the effect back to one bacterial surface molecule: sulfolipid-1 (SL1) - a well-studied virulence lipid.

SL1 rewires the functioning of the host cells. This lipid flips a switch in immune cells, which dramatically increases the number of lysosomes - the very organelles designed to destroy microbes. Why an Mtb virulence associated molecule should do this is a paradox emerging from this work.

On macrophages, the surface protein TRPV4 detects stretching or temperature by triggering a molecular cascade inside the cells. SL1 hijacks TRPV4 and eventually activates TFEB, a transcription factor that serves as the master regulator of lysosome production. Once switched on, TFEB triggers a flood of lysosome-related genes, sending the cell into lysosome overdrive.

When the team blocked TRPV4, the cascade collapsed. SL1 could no longer activate TFEB or increase lysosome numbers. When TRPV4 was activated directly, without any bacterial lipids present, it produced the same lysosome surge. This confirmed TRPV4 as a central switch for lysosome biogenesis, independent of Mtb.

“Lysosomes are central to macrophage defence since they degrade internalised pathogens, but at the same time, they also regulate many aspects of cellular metabolism and signalling. M. tuberculosis seems to exploit this complexity by modulating lysosome biogenesis,” says Umar.

“Umar’s study reveals a new way for cells to make lysosomes through the mechanosensor TRPV4. The role of mechanosensing in lysosome biogenesis, both in immune cells and beyond, is a new and exciting area to explore. The fact that this pathway can be exploited by M. tuberculosis virulence lipids adds a new dimension to host–pathogen interactions,” says Dr Varadharajan Sundaramurty, the principal investigator of the study.

Full link to the study: https://www.molbiolcell.org/doi/10.1091/mbc.E24-12-0560

0 Comments