Cancer cells are often imagined as rogue agents growing uncontrollably. But in reality, many cancers survive and spread as groups. In ovarian cancer in particular, cells frequently cluster together and float in the fluid-filled peritoneal cavity within the abdomen. These clusters are harder to kill and are more efficient at spreading to new sites in the body. How these cellular collectives hold together, fall apart, and reorganise remains poorly understood.

A study at NCBS set out to understand how the chemical environment surrounding cancer cells influences the way they organise themselves. Using ovarian cancer cells grown in suspension, the research team followed how individual cells assemble into multicellular structures and how these structures respond to changes in their surroundings.

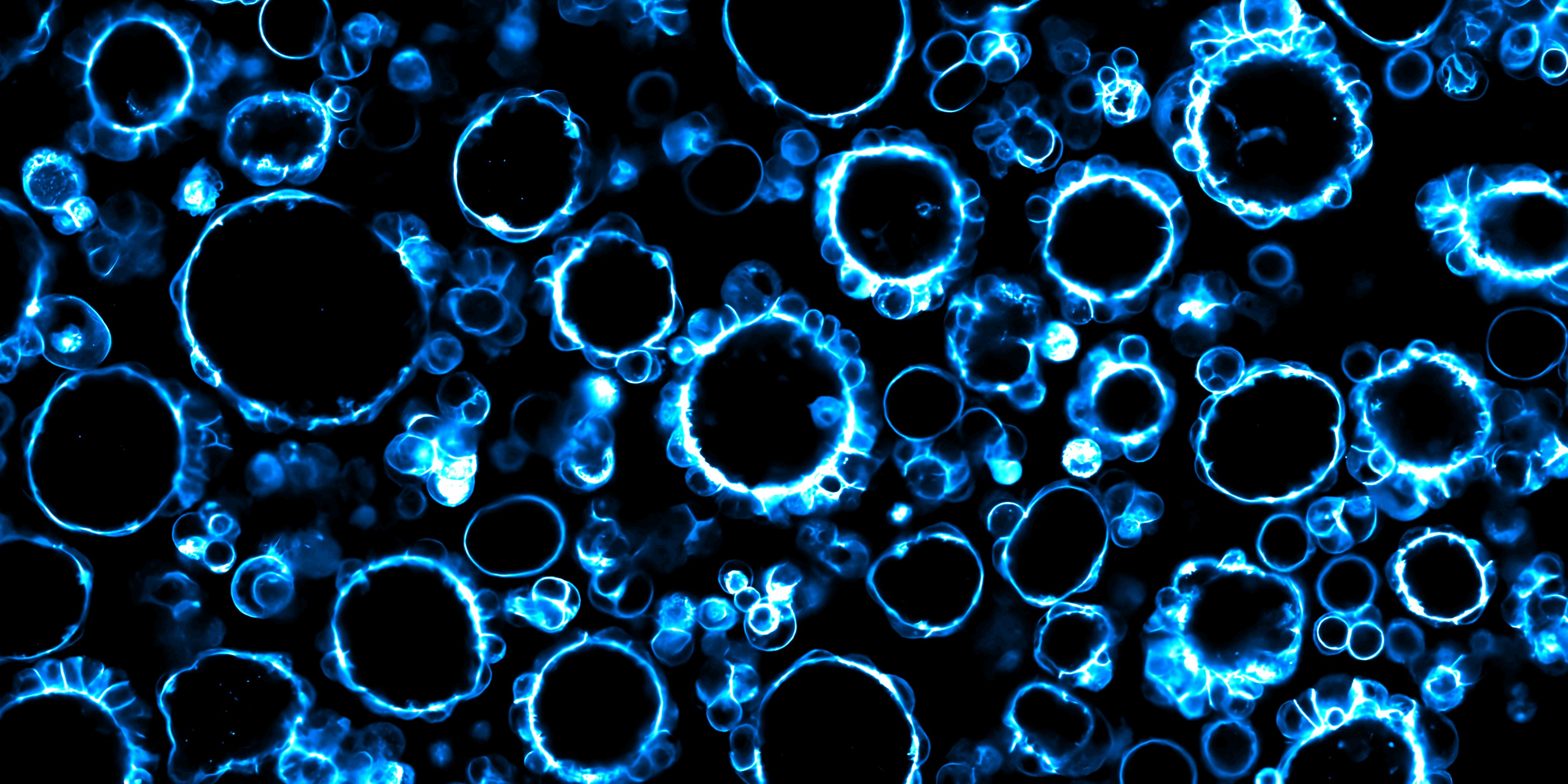

When grown in liquid, the cancer cells first came together as dense, irregular clumps. Over time, these clumps reorganised into smooth, hollow spheres with a fluid filled cavity at the centre. These hollow structures were not static. Instead, they repeatedly collapsed and expanded over several hours. “By closely tracking these changes using live imaging, we found that the shape shifts were driven by fluid moving in and out of the cavity,” says Sreepadmanabh, the lead author of the study. “These shape changes were closely linked to how strongly cells were connected to each other,” he added.

Cell - cell connections depend heavily on calcium, a chemical signal that stabilises junctions between neighbouring cells. When calcium levels were reduced, these connections weakened, causing the hollow structures to lose their shape and sometimes fall apart completely. When calcium was restored, the cells were able to reorganise and rebuild fully formed hollow structures, even after being dispersed into single cells.

However, this recovery had its limits. Strong or prolonged calcium disruption erased the cells’ ability to reorganise. This showed that calcium does more than simply hold cells together. It also sets the internal state of individual cells, determining whether they can participate in rebuilding complex multicellular forms.

The research team then turned to another key feature of the cancer environment: pH. In ovarian cancer, the fluid surrounding tumour cells can become more acidic as the disease progresses. When the team altered the acidity of the environment, they observed a very different effect. Acidic conditions stabilised the hollow structures, preventing their repeated collapse and recovery. Alkaline conditions, on the other hand, caused the hollow structures to reversibly shift back into dense clumps.

Unlike calcium, changes in pH did not reset the internal state of individual cells. Instead, pH controlled how the group behaved as a collective. “What this tells us is that different chemical cues are doing very different jobs,” says Sreepadmanabh. “Some act at the level of single cells, while others control the behaviour of the group as a whole.”

Together, these findings show that simple chemical signals can independently regulate different layers of organisation in cancer. Calcium determines whether individual cells are primed to rebuild complex structures, while pH controls the stability and behaviour of the multicellular cluster. This flexibility may help explain why ovarian cancer cell clusters are so resilient in the body.

“Our study highlights how cancer's spread is not only controlled by genetic changes but also by the chemical makeup of its environment. With just two knobs – calcium and pH – we can tune the form and fate of entire cell collectives” explains Dr Tapomoy Bhattacharjee, the principal investigator of the study.

Full link to the study: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/smll.202506120

0 Comments