Proteins are not always neatly folded molecular machines with a fixed shape that determines what they do inside a cell. Some proteins break all the rules. They exist in a flexible, constantly changing form, like clay - these are called intrinsically disordered regions, or IDRs. Their shape-shifting nature allows them to interact with many different partners and control critical cellular processes such as signalling, transport and gene regulation. Yet this same flexibility makes them extremely difficult for scientists to study.

Many state-of-the-art structure prediction tools stumble when it comes to IDRs. Even AlphaFold, which revolutionised protein modelling for well-structured proteins, gives low-confidence predictions when IDRs are involved. Traditional methods either ignore the IDR’s binding partner or assume a single fixed mode of interaction - neither reflects the diverse ways IDRs can bind.

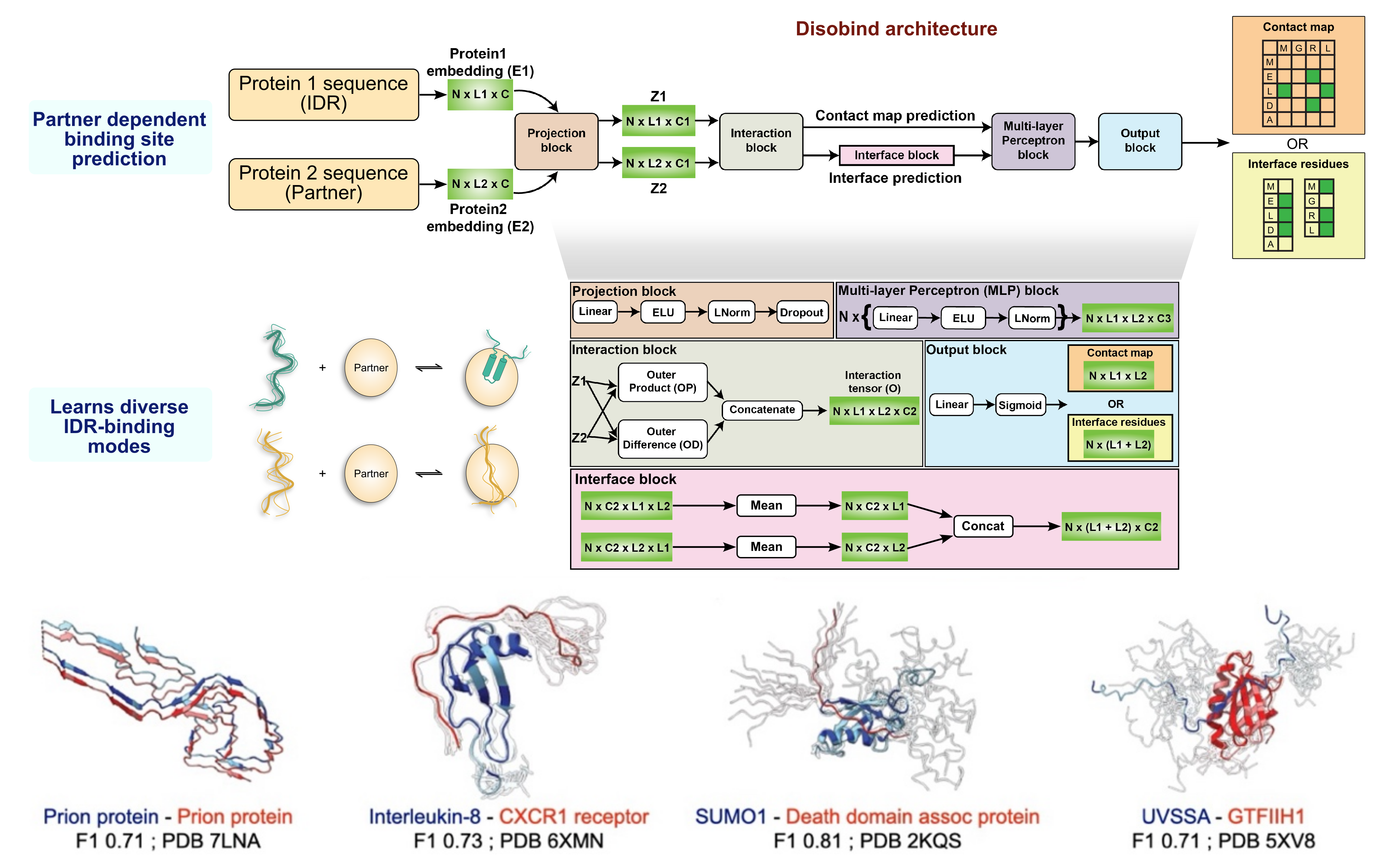

A recent study at NCBS developed a deep-learning model called Disobind that predicts how an IDR interacts with another protein using only their amino acid sequences. It captures which amino acids make contact when the proteins bind and identifies the “interface residues” responsible for the interaction. All without knowing the structure beforehand.

To train the model, the researchers collected hundreds of experimental IDR-containing protein complexes from multiple structural databases. These complexes capture different shapes adopted by an IDR while binding to the same partner. Using this dataset, the model learns where and how IDRs interact in the real world.

Kartik Majila, the lead author of the study, and his team tested Disobind on completely unseen proteins. It outperformed existing IDR interface prediction tools. It even beat AlphaFold-multimer and AlphaFold3 across multiple confidence benchmarks. And when the research team combined Disobind’s predictions with AlphaFold-multimer outputs, the accuracy improved even further. Disobind proved especially strong at predicting interactions in fully disordered regions where AlphaFold struggles the most.

The research team put the model to the test in real biological scenarios - including binding in prion proteins linked to neurodegenerative disease, communication between immune signalling molecules, and protein complexes involved in DNA repair and cell death pathways. Across diverse cases, Disobind consistently pinpointed which regions of the IDR become engaged during binding.

“Understanding where IDRs interact inside large molecular machines could help study complex cellular assemblies like the nuclear pore, chromosome remodelling systems or membrane scaffolds, where disorder is common. It may also help to design mutations that precisely tune IDR-mediated interactions. However, Disobind currently assumes that two proteins do interact, it does not yet decide whether a binding event will happen at all. Another challenge is that IDR structural data remains limited,” says Dr Shruthi Viswanath, the principal investigator of the study.

Full link to the study: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405471225003199?dgcid=author

0 Comments