Women in Science

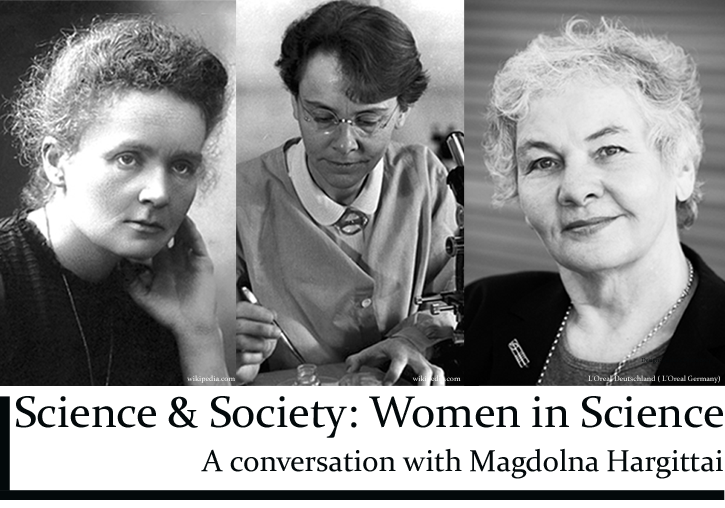

Photographs of M. Curie and B. McClintock from Wikipedia. Photograph of C. Nusslein-Volhard from L'Oreal Deutschland (L'Oreal Germany). Design by Aathira Perinchery.

Magdolna Hargittai, the first speaker in the Science and Society series, has been in the field of chemical research for over 40 years now. Her research interests range from structural, molecular and high-temperature chemistry to the intriguing subject of the personal aspects of science and women scientists in particular. She has authored and co-authored over a dozen books, including the highly successful Symmetry through the Eyes of a Chemist and the Candid Science series (and one on traditional Hungarian cuisine, Cooking the Hungarian Way). I had the chance to talk to her and here are excerpts from the interview.

Women in science: that's a fascinating subject. What sparked your interest in it?

My husband and I have similar interests and work in the same field - I was actually his first graduate student (smiles). Eventually, Istvan began interviewing famous scientists. We were always interested in the lives of scientists, but only as a hobby until then. Initially, the interviews were done for a magazine. Soon I joined him in interviewing scientists - many Nobel laureates and other prominent scientists. These interviews were published in the Candid Science series. We were well into this project when I realized that it was very strange that out of the 36 interviews in each volume, only 2 or 3 were with women. I knew that we were definitely not against women in science. I never before recognized that there was such a problem at all; I was busy with my science. But as I looked into this question I saw that there was a problem, and a serious one, for that matter.

That is when I started my own project: interviewing women scientists. I now have over 60 interviews with famous women scientists: Nobel laureates, presidents of universities and other famous women from about 20 countries.

So there is a potential book in the cards...

From the very beginning, I was planning to write a book on this topic. I haven't done it yet because I was too busy with all my other projects, my group, students, research. Even though we both are workaholics, there are only 24 hours in a day (laughs). Finally, I started working on the book a few months ago. I want to make it different from the Candid Science series. I don't want to do an interview volume, but rather write on the different topics concerning the problems of women in science, based on the interviews.

Being a woman scientist yourself in the late 1960s-early 1970s - how was it then, and have things changed now?

There were a lot of women in our group at the science university in Budapest, Hungary. Out of the 60 students who were trained as chemists in my class, at least half of them were women. There were women assistant and associate professors too - but there were no full professors. But this I did not notice at that time. I started working in my husband's group and actually here, there's a story worth mentioning. One day the director of our institute called my husband to his office and told him that although he knew that we both were doing very well with our research, it might not be a very good idea that both husband and wife work in the same group. My husband, quite bravely, answered, "All right, I understand. Tomorrow I will start looking for another job." Istvan had started a new field of research in Hungary and was very successful, and him leaving was the last thing the director wanted. And that problem was never mentioned again.

But it was rather early on in my career that I realised that I do have to have my own line of research. If I continued with Istvan, I would have never gotten recognition; everyone would have thought that the work was his and I was just an assistant. So I began to work with high-temperature inorganic systems and Istvan stayed mostly with organic molecules. That was a very important step in my career. From that time on, we rarely published scientific papers together. We did write books together, but that's a totally different story - it was a hobby.

Have peoples' perceptions about women in science changed over time?

Yes, perceptions have changed. In most European countries and in the United States it was in the late eighteen hundreds (in the 1880-1890s) that universities started to allow women to enrol. However, accepting them as professors and allowing them to teach was more difficult. I'll mention one example: the case of the famous mathematician, Emmy Noether. By formulating the invariance principles, she established the connection between symmetry and the conservation laws of physics. She lived in Göttingen, Germany. The famous mathematicians, David Hilbert and Felix Klein wanted her to join the mathematics department but the non-mathematician members of the Philosophical Faculty (to which mathematics belonged) voted against it, saying that it was unimaginable that all the young men coming back from the war be lectured at the feet of a woman. Hilbert angrily replied: "Why, this is a university not a bathing establishment." Later on she was allowed to teach under Hilbert's name, but without a salary. Eventually, Noether emigrated to the United States and went to Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania where she became a professor. In another case, even if they allowed a woman scientist to work, she had to use a separate staircase that was only for women to go to a laboratory. Discrimination at the beginning of the 1920s was still very strong.

Things have changed gradually. Women could go to study at a university and eventually they could get their doctorates. Then there was the anti-nepotism rule in the United States in the first part of the past century. This meant that a woman could not be employed by a Department of a University if her husband worked there. Several famous women, such as Gerty Cori and Maria Goeppert Mayer worked free for decades because of that rule. Now, of course, all that has changed.

From your research on the lives of women in science what would you say are the problems they come across?

This depends on the field of research and on the country. I have to mention that I have only been interested in the sciences and to some extent also in engineering and mathematics. Thus, I cannot comment on how early women were accepted into the humanities but it is possible that it was different from the hard sciences.

There is a serious dilemma that every woman in science faces: do I want a career or a happy family? And sadly, as different studies show, the best qualified women scientists are less probable to have a family. According to a study conducted in 2003, in Italy, for example, 29% of women professors of economics were unmarried (compared with 16% of the general population). In Germany, 71% of women physicists did not have children. This is a pity because, apparently, the presence of a family has a positive effect on the career opportunities of male scientists.

There are deep-rooted social attitudes concerning women in science: many think that the female brain is not cut out for science. It is then also interesting that the distribution of women in the sciences is very unequal; there are quite a lot of them in biology and medicine. While chemistry is somewhere in the middle, physics is the worst.

There is also the traditional masculine image of a scientist that women have to contend with. It is really a sociological problem. There was a study that looked at boys and girls in kindergarten and their responses to the covers of different science magazines. The pictures on the magazines were that of women doing something connected with science - sitting in front of the computer, working at an electron microscope or doing chemical experiments. The responses of the boys were the most interesting, and I remember two of them. One was that of a boy who said, "There's something wrong with this picture. She shouldn't do that." The next response was even more subtle: a boy described the given picture, constantly referring to the woman as 'he'. Why does a boy in kindergarten distinguish different occupations according to gender? Quite amazing. Of course, there are many things that can influence them, even at that early age. Take one example: I remember a recent advertisement that ran on television in Budapest and I saw similar ones in the US, too. It was an advertisement for a laundry detergent: a story of how the boys and their father were playing football and come home in dirty clothes, and the wife says that that is not a problem at all and then puts all the dirty clothes in the washing machine with the particular detergent. Why is it so obvious that the men play football and the women do the cleaning?

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1995. In connection with her I would like to mention how much she actually complained about discrimination. She emphasised that she was never discriminated against in her actual scientific work; it happened more in connection with administrative matters. She said she always got less lab space than her men colleagues, or smaller funds. When there was a position at the university for a professorship, and clearly she was the best qualified person, the department head told her that the fact of the matter is that there is another candidate - a man - who has a family: a wife and children, and he has to support them. She, on the other hand, had a husband who could support her. He got the professorship. She was still very bitter about this although this had happened much earlier than when we spoke.

You mentioned the Nobel Prize. Is missing recognition a big problem when it comes to women in science? How does it affect their careers?

Missing recognition is a problem. When it comes to missing Nobel Prizes for women, there are some very well known instances when the woman should have got it, but she didn't. The best known example is probably that of Lise Meitner. She was an Austrian nuclear physicist of Jewish origin who worked with Otto Hahn in Berlin. When the Nazis annexed Austria she became a German citizen and she had to flee from Germany to Sweden. Otto Hahn continued the work with Fritz Strassmann and they did the crucial experiment. But they could not explain what actually happened. Hahn kept up correspondence with Lise Meitner and she, together with her physicist nephew, Otto Frisch, understood what was happening and they explained it. Nonetheless, it was Otto Hahn alone who received the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1944 for discovering nuclear fission. There are other cases as well. But, I also have to say, that it seems that in recent years there has been a conscientious effort on the part of the Nobel Committee to award women. In the last three years there have been four women Nobel laureates in the sciences; one in chemistry (Ada Yonath) and three in Physiology or Medicine (Francoise Barre-Sinoussi, Elizabeth Blackburn and Carol Greider).

It is not only the Nobel Committees that are paying much attention to this problem lately. In the European Union, for example, there is a special committee looking at such gender related problems. They published their findings in huge volumes (called She Figures, the first one came out in 2003 and the latest in 2009).

What is the general trend? And what about trends across the different levels of science positions - from graduates to professors?

Based on the data from She Figures, when you look at the proportion of men and women in a typical academic career considering all fields, at the undergraduate level, there are actually more women than men. But after getting PhDs, the data can be represented as a scissor diagram. The number of women goes down and the number of men goes up. At the end, at the full professor level, there are only about 18% women. The situation in the hard sciences is much worse. There are already much fewer women than men to start with at the undergraduate level. At every step of the way, women drop out and fewer and fewer remain. This is what they call the "leaky pipeline." So by the time we reach the full professor level, there are only 11% women and 89% men. What is sad is that there is not much of a difference in the 2006 and 2009 figures. There is a very poor increase in the number of women. But if you look at the annual growth rate of women in science, it is about 6% for women compared to the about 4% for men in Europe.

Is there something that can be done to bring in more women into science, or retain the initial numbers at the higher levels?

There are, of course, many areas, where we can help. It is important that there be a work-life balance. Improved child care facilities, flexible working hours and parental leave conditions for men and women would help in this regard. Shirley Tilghman, the current President of Princeton University, for instance, introduced a 'tenure clock' system - meaning that men or women who have children during their tenure years can get an additional year before their tenure is up. Putting women in decision-making positions is also most important. Other crucial steps include eliminating the gender pay-gap, and providing role models - to portray women who achieved a lot in science and others, who besides having established themselves as good scientists, moved into high administrative positions, where they have the opportunity to introduce policy changes and improve conditions for women.

Your talk in NCBS was titled "Women in Science: Why We Need Role Models". Did you have a role model yourself?

(Smiles) This is something I thought about often. I don't think I had one. Originally I didn't want to be a chemist - I wanted to become an archaeologist. In my last year of high school, I had a fantastic history teacher and she asked me, "Are you sure about this? Hungary is such a small country and most probably most of the interesting sites have already been discovered. What would you do?" That was in 1964 - Hungary at that time was still a communist country. No one could travel outside the country without special permissions. So I realised, there was something in her words. I always liked chemistry - and so I became a chemist, as it was less dependent on political systems. And I'm really happy that I did.

What would you say you have learnt from these experiences with women in science? Has it changed the way you look at science?

Not at science itself, but at how it is organised on the human level, maybe. I have never had serious problems with the fact that I am a woman in science. But nonetheless, there have been ridiculous situations. For example, I was at a conference, where a man sitting opposite me said, seeing my badge: "I know your name. I know your husband's book on symmetry." "Which one?", I asked. The book was Symmetry through the Eyes of a Chemist. "Oh yes, I am also an author of that", I said. "Oh no, no. It's your husband's!" was the reply. At another conference in the US two years ago, a similar thing happened. I couldn't care less, but it was rather funny.

From science to using symmetry as a tool to bridge the gap between the humanities and the sciences: I find that really interesting. How do you visualize it?

I'll tell you how we started getting interested in symmetry. We knew it was important in molecular structure. Then when our children were born, we started taking photographs of our children and, along with them, of everything else. Then you notice flowers, trees and so on. How the petals of the flower go around, five or six of them and all equal. Or faces, fences, wall-paper patterns, etc. Such things are all examples of symmetry. So that led to the first book Symmetry through the Eyes of a Chemist, in which we practically went through the whole of chemistry from the viewpoint of symmetry and explained sometimes difficult-to-grasp ideas with ordinary, everyday examples. We also wrote a book for children in Hungarian explaining symmetry and that was quite successful and later appeared in Swedish, too. It has been used to teach the idea of symmetry in kindergarten.

Then this interest just grew and grew. An American publisher from California who had seen the Hungarian symmetry book for kids contacted us, asking us to write another one. That was a wonderful project because we wanted to put together something about symmetry for the lay person. So we wrote Symmetry: A Unifying Concept. Symmetry - bilateral, mirror, rotational, three dimensional - it's really everywhere. We discussed all this in the book. We had great fun. You also develop a sensitivity to noticing symmetry. Once my husband gave a talk somewhere on symmetry. The next day a woman came up to him, agitated, "You and your awful symmetry! I cannot stop noticing it since your talk." She looked angry, but it gave us a good feeling.

Symmetry appears in everyday life: in all the sciences, all the basic rules are symmetrical. There is symmetry in literature, in music - so it's really a unifying concept. Insects are symmetrical. Or, take the butterfly. Apparently, if the symmetry of their wings is broken in any way, then the other sex does not want to mate with them; it seems as if symmetry were a measure of their perfect, healthy nature.

Bridging the gap between the humanities and the sciences - do you think that is something scientists should be trying harder to do?

I think, yes. The scientists are the ones who should do something about it. The scientist knows more likely a little bit of music, literature, and anything else, but a writer or a musician seldom knows anything about science. That's the typical case of the so-called two cultures that C.P. Snow wrote about. Generally, scientists are supposed to know something about literature, music, paintings - but for a humanist it's cool to say "Uh! I don't know anything about chemistry."

There are a fair number of women researchers here in NCBS - what would be your message to them?

It is that just be sure of yourself and don't be discouraged if you ever come across barriers because you're a woman. Even if it might be difficult to balance the traditional role of a woman in society and the fascination of doing science as a career, do not give up. It may be hard and it requires the help of your family - but it is worth it a thousand times! If you feel that your call is science, go for it!

Comments

Good that problems of women

Post new comment