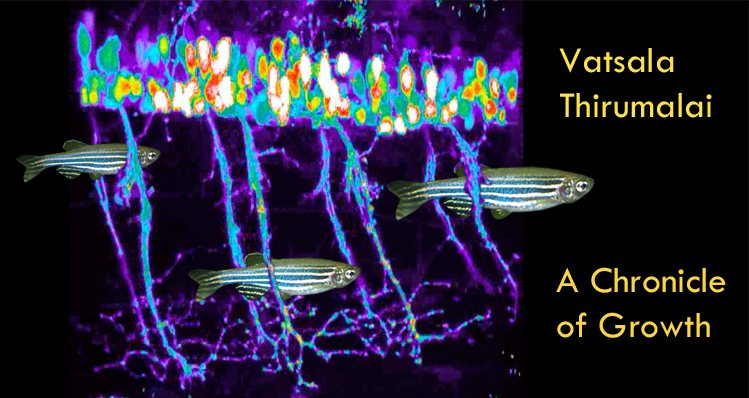

Vatsala Thirumalai: A Chronicle of Growth

Zebrafish 'swim' amidst the motor neurons that innervate their swimming muscles. Micrograph: Vatsala Thirumalai. Fish photos: wikicommons. Design: Geoff Hyde

Vatsala Thirumalai, a recent addition to the NCBS faculty line-up, can barely remember a time when she wasn't fascinated by neuroscience. In the interview below she tells how she is particularly interested in how the growth of the nervous system is coupled to the overall growth of an animal. A humble person, Vatsala explains her own growth as a developmental biologist largely in terms of the wonderful mentors she has had throughout her career.

G: How did you get into science?

V: I really was interested in neuroscience from the very beginning, that's what brought me into science. The interest in neuroscience came from two or three different avenues. One was that I liked biology a lot but if you looked in high school biology textbooks, then in physiology there are lessons on how respiration works, how circulation works, how the kidney works, and all that, but when you go to the nervous system, there was nothing really given in the textbooks. They only covered that simple monosynaptic reflex arc - you hit your kneecap and your leg flies up. And then they describe the different regions of the brain, cerebrum, cerebellum, spinal cord and so on. But that was about it. They never told you what was really going on in these brain regions, in the type of detail you would find for, say, the circulatory system. You know: all the chambers of the heart and how the flow goes from one to the next, through the lung, the oxygenation. When I asked my teacher Ms. Getsie about it, she told me that that was because we didn't know much about how the brain works. That piqued my interest in neuroscience. And on top of that philosophically I was interested in the nature of thoughts, why do we have thoughts, and what are they made of, is there a soul etc etc., so I really wanted to follow neurobiology and be a scientist.

G: How old were you at this point?

V: About 13 or 14. In higher secondary I chose maths, physics, chemistry, biology, and then I got into an engineering school but wasn't really interested in engineering. Luckily for me Anna University started an undergraduate program in Biotechnology that year. I belonged to the very first class. That involved a national level entrance exam with only about 15 places for all of India. It was good because I got into it, with the hope of switching from biotech to neurobiology at some point or another in the future. There were no actual undergraduate courses in neurobiology in India at that point. If you wanted to do related biological research you needed to go through a medical degree or you had to go through a BSc/MSc in zoology/ botany. If you look around the biologists in India today you will see they all have very unconventional trajectories to have got where they are now.

G: Were you getting support for your choices from you family?

V: With my family, I won the family lottery! I have the greatest family in the world. I have two elder sisters and an elder brother and all of us are academically very strong and all of us have done well in our careers. This is neither an accident nor did it come without planning and hardwork on the part of my parents. We are a middle class family with both parents in government jobs. From the beginning, my parents were clear that they would support their children in whatever their academic interest may be. They encouraged us to go and seek our dreams - be it a son or a daughter - they've taught us to have ambition in life and to work hard to get there. They have provided us with the best opportunities, the best schools. They were always willing to spend whatever was needed. And I had my elder sisters as my role models - the three of us went to the same school and I was better known as Vasanthi and Radhika's younger sis! They were both all-rounders - I followed their example in academics but shunned sports altogether! Being the youngest I had no family financial burdens, I did not have to go and get a job. Finance is just one part - to this day I get immense support and encouragement from my husband, parents, sisters and in-laws and that's what keeps me going!

G: Getting back to your BTech. Having talked to Ashwin, he said it was a very supportive intellectual atmosphere at Anna.

V: The BTech course was very unconventional for its time. Being an engineering university there was really no biological nucleus at the undergraduate level. It was strong for engineering but the director for the centre for biotechnology Dr. Kunthala Jayaraman brought very qualified engineers and chemists and biologists together to make this programme. For example two of the best hires that she made were Dr Gautam, who is still there, and Dr Guhan Jayaraman who is now with IIT Madras. So these people were fresh hires from the US and they were very good teachers. Both had a teaching method that was not directly from the book, there was no memorizing. They were geared towards total understanding of the material. Both their teaching and testing methods were focused on understanding of the concepts by the student, not rote memorization.

In that sense, you learned not just the material but the thought process. And I must say that I have imbibed a lot of Dr Gautam's thought processes in trying to analyse scientific problems, and that's what is key. If you are to be a scientist then you need to step away from the textbook and think about the material on your own. You have to be analytical and even if the textbook says this is so, then you have to question it, and ask what assumptions those concepts are based on. So in that sense it was a very good training period and of course Dr. Kunthala also emphasised having summer internships. Nowadays these are fairly commonplace, nearly all Masters programmes require an internship programme, but at that time it was very new. And so for nearly all of the summers of my four undergraduate years, I did summer research at IISc Bangalore, IIT Delhi, and my thesis project was done with Dr Gautam in CBT. So there was a lot of hands-on technical experience even at the undergraduate level, to see what lab work was all about.

And even though it was not neuroscience, it was still exposure to research methods. In those days we did not have internet access, so what you would do, is you would go and borrow a CD of Medline from someone and search the database for papers, or you would go the library, do you believe that, nobody goes to libraries anymore, you get everything online, but you would go through Biological Abstracts in the library. There was no email, no Internet.

G: Were any of those places particularly inspiring?

V: IISc was. I went to Dr Raghavan Varadarajan's lab in MBU, the Molecular Biophysics unit, I spent two months there, I did some protein purification. It was fun to be part of such a young atmosphere, to see students doing research on their own, you didn't have to worry about anything else, food was available at the messes, all you had to do was to show up on time, but the rest of the time you can just spend in the lab. That was fun, I made some very good friends too.

G: And where to from Chennai?

V: I finished my BTech in 1996. I decided that I would go to US for graduate education in Neuroscience. Among the places I got into, was Brandeis University. Picking the right place was not easy, you had to physically go to the US Consulate to go through the Peterson's review, again there was no Net to do this then. The consulate in Chennai had a library with a copy with reviews of all the different universities, so you can sift through the descriptions of each faculty research programme. Brandeis appealed to me because it was a small university, with only about 50 life-sciences faculty. But they worked on problems ranging from single-celled amoeba all the way up to cognitive brain science. It was a lot of things happening in a very small place. I also got in at NCBS, I came here and interviewed in '96, and was accepted, but because I wanted to focus on neurophysiology, I thought Brandeis, at least then, would be better suited to those types of questions.

G: How was Brandeis?

V: My PhD was a life-changing experience. In the first year they had a full-year rotation system, where you moved through different labs and funny enough I didn't end up in any of the labs I rotated in. The lab I did my PhD in was Eve Marder's. She had a joint lab with Larry Abbott who is a computational neuroscientist. Eve and Larry collaborate closely and there were a lot of interactions between these two labs. I did one of my rotations with Larry and in the course of interacting with members of Eve's lab I got very interested in the sorts of questions they were working on. So I decided to just try it, and did some lobster dissections on some free afternoons.

G: I've heard about these lobster labs, do you eat lobster?

V: No I'm a vegetarian. But what we would do, would be to freeze all the tails and claws, because we would not use them, and then once a summer we would have a barbeque for the entire biology department. We made lots of friends that way!

Meeting Eve was what I would call my life-altering moment. Eve is the kind of person who does not think of herself as just a PhD advisor, she takes her mentorship very seriously. She is amazing. I learnt everything from her right from scientific methodology through to a lot of neuroscience concepts. At this point today I still go to her if I have any sort of questions or dilemmas - things that I want to clarify myself. She continues to be my mentor and I'm sure that she does that with a lot of postdocs and students, she takes personal interest in their success. I was lucky to have her.

She had a very systematic approach to science. I will give you one example - lab notebooks. She had a system that I want to replicate in this lab. There is a master notebook, which has a record of every notebook ever issued in the lab. And the notebooks themselves were stored in the lab according to number - anything that you want to know, you just go to the masterbook., You will usually know which person did what experiment, so you look through the books in their list, and next to the record for each book there will be a brief overview of the experiments covered in that book, so that will lead you to the book itself. And then you can pull out the raw data from the book.

I know it's getting increasingly difficult these days when everything is digitised, so students don't even have a notebook. But they should because then you lose out on these tiny tidbits of knowledge. Sometimes the information from an experiment is not immediately obvious, often it's only after a period of time, when you have gathered enough evidence that the new idea jumps out at you.

And Eve was someone who was very good at organising teams. Getting the information from an experiment packaged into a paper, that requires a lot of skill. Not all the pieces of data are suited to going into a paper in a very straightforward way. Sometimes you need to do a bit of juggling - you have to bring in a person with a specific expertise, say a theoretician, to do a little bit of modelling so the overall point of the paper becomes emphasised. Those kinds of things she is very good at, and I have observed first-hand how she ropes in different people to get the information out into the public domain, in as little time as possible. That's something I want to emulate.

And to add one more thing, she was very good about reading. She would have personal subscriptions to a lot of journals, Journal of Neuroscience, of Neurophysiology, Nature and so on, which could come to the lab, and she would go through these and mark out the articles that she thinks are interesting, and that the lab members should read. She has an amazing ability to recall. If you go and chat with her about a particular scientific problem she would be able to recall which paper, and which figure in that paper, would be relevant to that particular question. To have a fine scientist like that as a mentor means a lot and so I hope to be able to catch at least some of those qualities.

G: So what types of things were you working on at Brandeis?

Movie of zebrafish motor neurons labeled with GFP using Hb9 promoter and Islet-1 promoter. Vatsala Thirumalai.

G: So what do we know about the process?

V: We don't have a full understanding, but what we do know is that there is constant turnover of the neuron's membrane, so just by adjusting the rate at which new membrane in inserted, and making sure that the new bits have the required proteins that a nerve needs, then that can allow for growth.

G: And the overall growth of the organism could then provide a stretching mechanism?

V: Right. And I also became interested in synapse formation, and circuit assembly,. How is it that circuits produce function in the context of the motor systems? Motor function is needed early in life, an animal needs to be able to move. In humans before you get a lot of the different higher cognitive abilities, you do get locomotory abilities.

And this brings me to the research that I did after I finished my PhD, and started to do as a postdoc at Cold Spring Harbor. I couldn't do the research on lobsters because they take so long to develop and it's difficult to get the embryonal stages during various times of the year. So zebrafish seemed to be an obvious choice because it's a developmental organism and it's possible to study swimming motor behaviour. Of course it's also well suited to genetic manipulation.

Around this time Holly Cline at Cold Spring Harbor (CSH) labs wanted to start zebrafish work. Historically, her lab has studied sensory systems, development of the visual system in tadpoles, but she wanted to expand into zebrafish because of all their advantages. I went there with the mandate that I would set up a zebrafish facility there, but would be free to choose my own questions. There was no-one else studying zebrafish at all in CSH at that time. I was sometimes growing the fish up to the full adult stage, so I had to learn how to grow paramecia, brine shrimp - I was a single-woman army!

Then I started to look at how swimming motor patterns are generated in zebrafish larvae. I would look at how episodes of swimming were generated in different larval stages.

G: I was very intrigued by one of your results there. You were able to show that larvae at 3 days already have certain abilities, but they don't express them until 5 days, because the expression is being held back by dopaminergic neuromodulation. Do the juveniles of other organisms have such "untapped talents"?

V: Yes, probably one of the best examples is in the frog where the neural centres for breathing are all ready to go even at the tadpole stage but they are held back until metamorphosis in an analogous fashion to the delayed expression of advanced swimming behaviour in the zebrafish.

G: You and Eve wrote a major review on neuromodulation and one of the points made was that it was an under-appreciated phenomenon: is that still the case?

V: No, I would not say that. I think the role of neuromodulation in neural circuits is becoming more and more apparent, especially because now we have a lot of these tools that allow us to actually see these neurons in action. In mice it's becoming possible to make transgenic animals that have channel rhodopsin in their dopaminergic neurons. You hit them with blue light and you can see their behaviour, That's just one example, but now with all of the studies done with invertebrates, not only from Eve's lab, but also from people like Ron Harris-Warrick in Cornell we have seen that neuromodulators can do a lot of very important things for neural circuits. And such circuit thinking is really shaping all of neuroscience, not just invertebrates.

G: What did you learn about doing science in Holly's lab?

V: Well it was a long postdoc - six years - because it was starting from scratch. It turned out really well because I learned how to be independent. Holly was very encouraging, very supportive, but at the same time, she let me do my own thing. I fell down, got up, fell down, got up.

G: Sounds like a perfect postdoc!

V: Yes! Another thing I learned there was how to bring everyone in the lab into the writing process. Any paper that came out of the lab was discussed by the entire lab, we would all give inputs. Each manuscript was discussed multiple times. Even before the paper was ever begun we would always discuss each member's data as the experiments proceeded. Once the data crystallised into something publishable, the person would first present a figure list, of the ones they thought would go in the paper. We would offer our criticism about what other data might be needed. When it got to the manuscript version we would all read that, and give comments about both the text itself and the weaknesses in the scientific argument. How a reviewer might perceive this claim versus that, how the writer might rearrange things and make it stronger. So this was very good training for writing and submitting manuscripts. And when the reviews came back, these would be discussed in the lab again.

Holly also has very wide interests. Even though most of her work was focused on tadpoles, there was my work on zebrafish, she has a paper with someone else on CP element-binding proteins and their effect on dendritic morphogenesis, she has a paper on electron microscopy of synapses in Xenopus - she uses a lot of different techniques and systems. And she is equally at home with all these different approaches. She can understand and critique the data wherever they come from.

Having been in that diverse atmosphere and watching Holly as a mentor for all these different topics, it was good for me to realise that this did not necessarily lead to spreading things too thin. Eve had a different, more tightly focused style, and I learnt a lot from both ways of doing science, they both have their appeals for me.

I also learned a lot from the other postdocs in the lab - there were about seven who overlapped with me. Many of them are PIs now in different parts of the world. CSH, like many other US institutions, runs on postdocs, and when I was there I was invited to be part of a postdoctoral working group, so as to work out how to attract the best people from around the world. And also how to improve postdoctoral life, increase people's chances of transitioning to faculty positions or whatever position they may wish to go to. We held monthly discussions on issues ranging from immigration, to housing, to publications, to ombudsmen, and so on and so forth. I think the guidelines are now integrated into a postdoctoral policy.

G: Can you bring them into effect here?

V: (laughter). It may be useful to do something like that.

Another good feature of CSH as an institution was that it had so many courses and meetings, just like NCBS, happening every summer. There are many interesting long-term courses: Molecular Techniques in Neurobiology for instance, Ion Channels, Imaging in Nervous Systems. So the best people from all over the world would come to CSH to conduct these courses every year, so you could meet them, go to the courses and learn so much. And there were meetings of course, so many, both at the main institute and at Banbury, which is a small conference centre a little bit away from CSH. Shona has been there as well.

G: And from there it was on to NIH?

V: Yep. At this time, in 2008 when I finished with Holly, I applied to join NCBS and got the position here, but the lab space was not ready. I had agreed to go to Michael O'Donovan's lab in NIH before I got the NCBS offer, so I talked to Vijay here and it was mutually agreed that while the lab was getting ready I could spend a bit of time with Michael O'Donovan. So the initial plan was to just be there for a year but then something exciting happened, we had a baby, so one year became two and in 2010 I'm finally here.

G: I've read the outline of your research plan in the NCBS Annual Report, where you talk about following up your earlier work on the role of the dopaminergic neurons in the development of zebrafish locomotion: is that a good summary of where things are headed now?

V: I will be continuing in that line. But another question I'm interested in is the role of electrical coupling in the maturation of neurons, so that might be something I follow up as well.

G: So have you started collaborating with people at NCBS?

V: Absolutely, I just finished teaching the Neurobiology course with Upi, Shona, Vijay and Sanjay, and I do talk informally with a lot of the Neuro folk here. We are also planning a shared imaging space with multi-photon microscopes. Madhu and I are talking about how to hook up neurons to computers so that might be something that shapes up over time. And I'm sharing the lab space here with Raghu so that naturally leads to lots of chats.

G: So you will be looking for some new recruits from the next intake?

V: Yes, and I will have some summer interns, I have one coming via the NCBS-Cambridge programme, and perhaps one more from Harvard. With the new students I will just be patient and take one by one.

G: And how have you found being back in India?

V: Oh, lovely! Especially the last six months I've been living on campus, and it's like being in heaven, surrounded by such greenery, birds, and being so close to work, that's been a real boon.

Comments

Hello ma'am, it was indeed

hello mam, The research

Dear Vatsala madam, Women

Thanks Aruna. This is indeed

Post new comment