Under Threat: the shrinking world of the Ganges River Dolphin

Our increasing demand for fresh water, and our tendency to cluster ever-more densely around its sources, are not good news for freshwater habitats such as rivers and lakes. These come under a depressingly diverse range of pressures. Natural river courses are toyed with, and dammed as the ultimate insult; pollution pours in from both urban and rural practises; motorboat traffic tears at the shoreline and riverbank; and exploitative hunting and fishing can turn a waterway into a graveyard. Even the most sacred stretches of India’s revered Ganga are not spared: in Varanasi, raw sewage and industrial waste spew into the river from over 30 outlets, raising the faecal coliform count by a factor of 25, to 1.5 million counts/100ml at the city’s downstream limit, according to Mishra, 2005.

Not surprisingly, the denizens of freshwater habitats are some of the most threatened of the planet. For example in North America the extinction rate of freshwater fauna is five times that of terrestrial fauna. And, as in tropical rainforests, scientists are desperately trying to discover what wonders these habitats contain before they disappear forever. About 200 new species of freshwater fish are, for example, described each year.

The plight of India’s flagship freshwater species, indeed its “National Aquatic Animal” - the Ganges River Dolphin - is the focus of a recently published study by Nachiket Kelkar (see abstract here), based on fieldwork done while he was a student in the M.Sc Wildlife program at NCBS (run together with the Wildlife Conservation Society-India and the Centre for Wildlife Studies). Since the Yangtze River Dolphin was declared extinct in 2006, there are now only four species of river dolphin left in the world. The Ganges River Dolphin is classified as “Endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. While its ecological role as a generalist feeder actually makes it less sensitive, as a barometer of overall river health, than the Critically Endangered Gharial (a crocodilian), its charismatic appeal draws public sympathy to the cause.

Nachi took to the field as an aquatic war correspondent, documenting the battle for resources between dolphins and fishermen in the Vikramshila Gangetic Dolphin Sanctuary in Bihar. This 60km stretch of the Ganges was designated in 1991, and under the guidance of Dr Sunil Chaudhury (one of the co-authors of Nachi’s paper) much has been done there to keep up dolphin numbers - despite this area being one of India’s poorest and most populated. Nachi went into the study without any preconceptions, with no pet hypothesis to test. His main approach was to see if dolphin numbers along the river bore any relationship to features, either of the river itself (e.g. depth, flow speed, riverbed type) or of fishing practises (e.g. frequency of boats, net use).

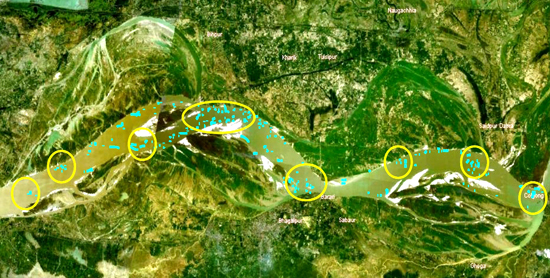

Blue rectangles represent dolphin sightings along river stretch in Vikramshila Sanctuary. Sightings were clustered (yellow circles) and the same areas were also favored by fishermen (not shown). Prepared by Nachiket Kelkar.

Interestingly, Nachi found that dolphins and fishermen were strongly drawn to the same parts of the river: shallow areas with muddy, rocky bottoms, or deep mid-channel waters. Fishermen and dolphins both cluster in these areas because they are the richest in fish, which make up most of the dolphin’s diet. Dolphins appear to be able to tolerate the presence of fishermen, but would avoid the good spots if too many boats arrived.

By examining the stomach contents of dolphins strangled by fishing nets (a major local threat) and comparing these with the fishermen’s catch, Nachi found that the fish hunted by both man and dolphin are small. This is probably what the dolphins naturally prefer, their slender, toothed beaks ill-suited to large items. The fishermen however have been forced to focus on the smaller catch, since, as is the normal outcome of long-term overfishing, the average size of fish in the Sanctuary has been steadily decreasing. In fact, based on the the mandated minimum length of fish catch, about 75% of the fishing effort in the area is now illegal.

Nachi found evidence however that in a different way, it is sometimes the dolphin’s hand that is forced. As the dry season took hold, dolphin sightings increased by 50%. Dolphins are thought to prefer smaller river tributaries, but with so much water being drawn from the Ganges, in the dry season they must seek main channels like those of Vikramshila.

So as the fish get smaller, and the streams get shallower, dolphins and fishermen have become, more than ever before, unwilling river-bed mates. To reduce the conflict, the tape must be put in reverse: fish must get bigger, streams deeper. The second goal is the tough one. As Jagdish Krishnaswamy, another author on the paper, says: "We need to get the balance right. Of course the local people need access to the river water and its resources, and upstream diversion of water for irrigation will take place, but we must sustain adequate flow for fish, dolphins, otters and the overall health of the ecosystem". In the short-term, the first aim is more achievable. Nachi and his co-authors suggest stricter policing of illegal fishing, and even more realistically, the provision of alternative income opportunities for fishermen who opt to diversify. Education will be important too, and has previously been a very effective tool in the area. In the very short-term, if fishermen know not to bring too many boats into their favourite spots, there is a chance of a tolerable truce.

Comments

NAchiketa, pl share your

Post new comment