Dark times for tigers?

The fragmented forests of the night might soon be darker places, with fewer tigers to brighten them. How is this possible when recent census reports show rising tiger numbers in India? A study by scientists from the NCBS and Cardiff University shows that mere counts are not enough. Current tiger populations in India have lost 93% of their former genetic variation, information coded in genes, vital to species' survival. Also, the populations are not interbreeding like they used to, becoming isolated in fragmented habitats. The authors warn that this motif could portend decline, even extinction, of the endangered big cat in India.

A painting by Ghulam Ali Khan in 1820, depicting a tiger hunt in Rohtak District, Punjab, India. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Then and now

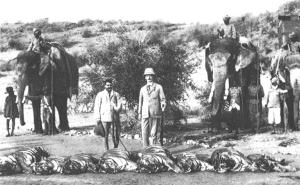

The extinction of tigers is something the Mughals would have never imagined, when they invaded India more than 500 years ago. Tigers were far more numerous then and persecuted too, a fact historical records prove (see inset on left). Tiger hunts were a matter of pride in the more recent era of British colonial rule as well. During the late 1800s and early 1900s alone, an estimated 80,000 tigers were killed in such hunts. Alongside this decimation, large-scale logging of forests and clearing of land for agriculture and human settlements destroyed tiger habitats across the country. Available habitats shrunk and consequently prey counts dwindled, slumping tiger numbers further by the 1970s. Today, fewer than 1800 wild individuals survive in India.

Tiger trails

Population declines such as these leave tell-tale signs in the genes of animals, something a detailed genetic analysis of the DNA from their skin or bone can reveal. Such methods also give insights into the diversity and variation of genetic material in the species, which is critical to species' survival, helping them adjust to changing environments. Furthermore, scientists can tell from genetic signatures whether different populations of a species distributed across a landscape are interbreeding, a requisite important to maintaining genetic diversity in the species.

Scientists Samrat Mondol and Uma Ramakrishnan of the NCBS and Cardiff University's Michael Bruford used these genetic tools to profile the Indian tiger, past and present. Had tigers lost genetic variation due to population declines? Had the genetic diversity of current tiger populations distributed across parts of India changed? To answer these questions, they first collected tiny bits of tiger skull and skin from specimens at the Natural History Museum in London and National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. Mondol extracted DNA from these - a simple-sounding, but extremely delicate task to accomplish. Most museum specimens are old, and age wears down DNA, as do curing processes that specimens undergo. The oldest sample Mondol worked on is 154 years old - despite that, Mondol obtained large segments of DNA from these samples, a feat that strengthened the results greatly. To understand how tigers are shaping up now, the team analyzed DNA from tiger faecal matter collected across Indian reserves three years ago.

The story

The results tell a startling story. The maternally-inherited genes that the team analyzed show that modern tigers have lost as much as 93% of the genetic variation seen in the historical populations. "It's possibly because of an interaction between behaviour and genetics," says co-author Ramakrishnan, Professor at NCBS. Female tigers mostly inherit the territories of their mothers. As a result, certain genetic variations could become tied to specific locations. As tigers become extinct in such areas, there is an irreversible loss of that variation.

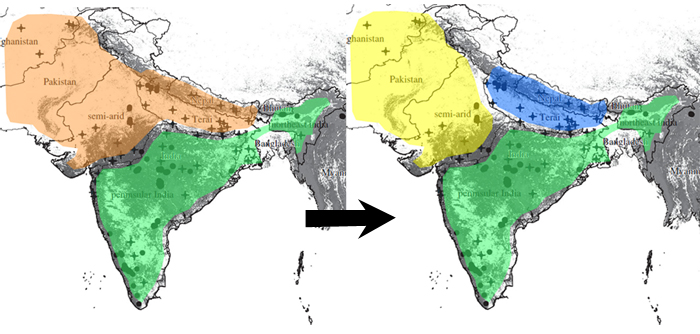

While she agrees that it is interesting to learn what was lost, Ramakrishnan, who has been using genetic tools to study tiger populations since 2004, points out that there are even more significant outcomes from the study. The older museum samples reveal that a century ago, there were only two distinct tiger populations: tigers in peninsular and north-eastern India formed one population, while tigers in north India (including the semi-arid regions of Afghanistan, Pakistan, Rajasthan and Gujarat, and the Terai at the foothills of the Himalayas) comprised the second. This meant that tigers within each population were interbreeding and exchanging genes, thanks to connectivity between landscapes in each cluster. But modern samples show that there are currently three distinct tiger populations in the Indian subcontinent. The historical north Indian population has now split into two, with the semi-arid tigers being distinctly different from the Terai individuals (see inset below, From Two to Three). "The population of tigers in the semi-arid region seems to have been isolated. And from a perspective of where tigers are there today, they exist only in Ranthambore and Sariska. So those tigers, according to me, are in danger," says Ramakrishnan.

From Two to Three: Historically (map on left), tiger populations were comprised of two: the peninsular and northeast Indian population (in green) and the north Indian population (including tigers in the semi-arid areas and the Terai) in orange. Contemporary populations (map on right), are divided into three: the semi-arid tigers (in yellow), the Terai tigers (in blue) and the peninsular-northeastern tigers (in green), each being distinctly different from one another. (Map adapted from Mondol et al 2013).

No corridors

The results leave no room for doubt: the impacts of loss of habitat connectivity are clear. Available habitats that began to shrink decades ago are today shrinking further. Worse still, they are now fragmented, due to conversion and destruction of smaller reserves that link habitat patches to each other. Tigers can no longer traverse safely over contemporary landscapes, and have been isolated from each other for too long - a story their genes clearly portray. The scientists believe that the trend "represents a conservation red flag", warning that extinction of the species may not be as far off as we imagine it to be.

With such a gloomy prediction, the study has been the focus of numerous articles in the media. "But there is also a lot of good news in this paper that many journalists have not focused on at all," says Ramakrishnan. Tiger populations across peninsular India still come across as one cluster, both in the past and present. "This is really interesting," she says. Peninsular India includes two large tiger landscapes: the forests of central India in the north and the mountains of the Western Ghats to the west. To the east nestles the smaller Nagarjunasagar Srisailam Tiger Reserve (NSTR). The current study implies that there could be connectivity across these landscapes, something they have not investigated yet but plan to in future.

And the authors are hopeful. "Maybe we can maintain this connectivity. But we have to talk about it," she says. "That's the other point of this paper - that the talk in conservation is always about numbers. But that's just not enough. Increasing numbers of tigers in Kanha National Park from 51 to 55, for example, is not enough for the species. There has to be connectivity. Which is of course, more than just numbers." Ramakrishnan feels that this also means pepping up protection in existing habitats which are now being ignored since there are fewer tigers there when compared to larger Protected Areas such as the National Parks of Kanha in central India and Bandipur or Nagarhole in the south.

Cick here to access the paper "Demographic loss, genetic structure and the conservation implications for Indian tigers" published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Comments

Sir, Why is this change" from

Your first question is valid

Post new comment