History of Indian Healing Traditions

Alternative healing systems have always been part of Indian tradition: from local medicine men to the vaidyas or physicians of the more classical unani and ayurveda. The popularity of these remedies took a beating with the advent of allopathic medicine. But traditional medical systems are coming to the fore once again and enjoying renewed interest. Two scholars, Indudharan Menon and Anna Spudich, of the Science and Society project at NCBS are spearheading work on the history and existing practices of some of these Indian healing traditions, documenting them for the generations to come.

The People

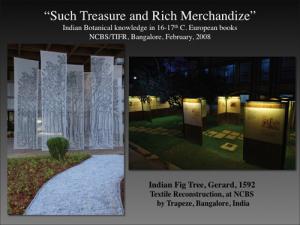

Anna Spudich joined NCBS as a Scholar-in-Residence in 2006. Formerly a cell biologist at Stanford University for 25 years, a chance glimpse of an illustration of an Indian Ficus (banyan) tree in a 'herbal' (some of the earliest books that dealt with herbal medicines) piqued her interest in the traditional botanical medical knowledge of India. In early 2000, she left the field of cell biology to initiate study of several traditional healing practices. To get an overview of the field, she met ayurveda physicians, medicine men of the Irula (a tribal group based mostly in Tamil Nadu) and Carmelite monks in Kerala who treated snake bites. She also studied historical records of Indian medical therapies in the pre-colonial period. Based on her research on several 16th century European works on Indian medicine and the 17th century twelve-volume text of Hortus Malabaricus, she curated an exhibition at NCBS in 2008 titled "Such Treasure and Rich Merchandize: Indian Botanical Knowledge in 16th and 17th Century European Books", which is now on permanent display at the Regional Museum of Natural History in Mysore, Karnataka. The Hortus Malabaricus garden (see inset photograph) was developed as part of the exhibition. In 2009, Spudich together with Rainer W. Bussmann (William L. Brown Curator for Economic Botany at the Missouri Botanical Garden, USA) organized an international conference at NCBS titled "Indian Traditional Knowledge: History, Influences and New Directions for Natural Science". The conference brought together scientists, historians and healthcare professionals to examine the contributions of Indian traditional knowledge to science, social history and health care.

Spudich was soon followed by Indudharan Menon who joined the program as a Visiting Fellow in 2008. A scholar of Indian healing traditions for the past 36 years, Menon had spent several years in Benaras, Kolkata and Nepal studying the various forms of ayurveda as well as other local healing traditions after his graduate and post-graduate studies in philosophy. He has conducted research on ancient Indian manuscripts in private and public collections for the Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies project. The author of a book on Buddhist tantras "The Concealed Essence of the Hevajra Tantra" based on his work in Nepal, Menon is also a skilled player of the sarangi. He studied several classical texts of ayurveda like the Charaka Samhita and Ashtangahrdaya under the doyens of ashtavaidya ayurveda practice in Kerala and worked closely with famous vaidyas and scholars there.

The Ashtavaidya Project

The ancient tradition of ashtavaidya ayurveda is one of the healing systems Menon and Spudich had begun documenting over the past three years, before the formalized Science and Society program came into being. The ashtavaidya healing tradition incorporates both ayurveda and local folk techniques, and is currently practised by just six families in Kerala. But ashtavaidya ayurveda is not just seen as a healing tradition: its many facets overlap with "sociology, medical history, the history of Kerala and folk healing as well," as Menon puts it. "The ashtavaidyas maintained a classical practice, preserving a long tradition that has been maintained over centuries," he says. Traditionally, the practice has been handed down from generation to generation in the ashtavaidya families. Sons would apprentice with their fathers and grandfathers. Studying to become an ashtavaidya meant many years of learning and training under the tutelage of a senior ashtavaidya practitioner. Every apprentice had to dedicate a whole year or more to learning the sacred text of ayurveda, the Ashtangahrdaya. Medicines used to be tailor-made for each ailment and individual. "But it has been undergoing changes: there have been a lot of experiments and new ideas coming in, obviously with the interface with modern medicine," says Menon. Now, ayurveda physicians even use modern aids like MRI scans to diagnose ailments. Medicines are no longer tailored for individuals; they are now manufactured on large scales to meet a growing commercial demand. So for the History of Indian Healing Traditions team, the reasons for documenting this dying tradition were many.

The first step was to interview the existing practitioners of ashtavaidya ayurveda and their families in Kerala. Spudich and Menon conducted and video-recorded these interviews. These interviews shed light on a number of issues the practitioners felt were plaguing their tradition. "The older and younger ashtavaidyas had very different things to say. The older people had experienced another world. Vaidyamadham for example, has a very critical attitude - he says that the current system does not educate students enough to make them vaidyas," says Menon. Many ashtavaidyas felt that there was a need to educate the public about the basics of ayurveda. Menon and Spudich have highlighted these and other issues in their paper in the Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine in 2010 titled "The Ashtavaidya physicians of Kerala: A tradition in transition" (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3117315/). The Indian journal Current Science featured an interview with Spudich and Menon about their work with the ashtavaidyas (http://www.currentscience.ac.in/Downloads/article_id_099_04_0427_0431_0.pdf).

Spudich and Menon will soon be making more of their work accessible online. "The (Science and Society) website will have links to the actual recordings of the interviews. Our goal is to also create an oral history archive on the living ashtavaidyas," says Spudich. Both Spudich and Menon are also currently working on a monograph summarizing all information collated during the ashtavaidya project. "It will also prepare the ground for our proposed study of other Kerala healing traditions," says Menon.

Healing Traditions: More In Store

The healing traditions Menon and Spudich plan to document in the future include various therapies predominantly practised in Kerala like maanasika chikitsa (the treatment of mental disorders), visha chikitsa (poison therapy) and baala chikitsa (pediatrics). Unlike the ashtavaidya tradition, these folk traditions are not based on texts. "This will involve more work than the ashtavaidya project - folk healers are not very eloquent with ideas unlike the ashtavaidyas," says Menon. Ritual and faith play a huge part in these healing techniques and they will be looking at this aspect of folk traditions as well while recording it. "We will also be documenting whatever is left of tribal practices in Wayanad," says Menon. "These tribal practices are also changing now." These changing traditions mean that a lot of ancient information will soon be lost forever unless someone takes the pains to archive them, as Spudich and Menon are hoping to do.

And deciphering ancient texts that have already documented medical practices is also equally important. "I'm continuing work related to the Hortus Malabaricus project by translating the 16th century text by Cristobal Acosta," says Spudich. Cristobal Acosta was a Portuguese physician and naturalist who pioneered study in oriental plants. During his visit to Kerala as the personal physician of the Goan viceroy in the 1560s, Acosta documented the Indian botanical medical practices prevalent at that time in a 385-page document Treatise of the drugs and medicines of the East Indies. Written in Castilian Spanish (a relatively older dialect compared to modern Spanish), the text would be difficult to decipher even for a native speaker of Spanish. Spudich is currently working with a Spanish professor who specializes in the dialect. He will give Spudich literal translations of the text, which Spudich will put into context using her knowledge of other ancient texts like the Hortus Malabaricus and 16th century physician Garcia de Orta's Conversations on the simples, drugs and medicinal substances of India. This will give us another resource that will throw light on traditional botanical medical practices in India.

More details about Spudich and Menon's work are now available on the Science and Society website that was launched recently. You can access their updated work on the History of Indian Healing Traditions section here: http://www.ncbs.res.in/HistoryScienceSociety/IndianHealingTraditions. Comments and suggestions are most welcome, say Menon and Spudich. With the renewed interest that traditional healing techniques are experiencing, their work comes at the right time. Knowing the basis of ancient knowledge better could potentially open up more questions for scientific enquiry.

Comments

Post new comment