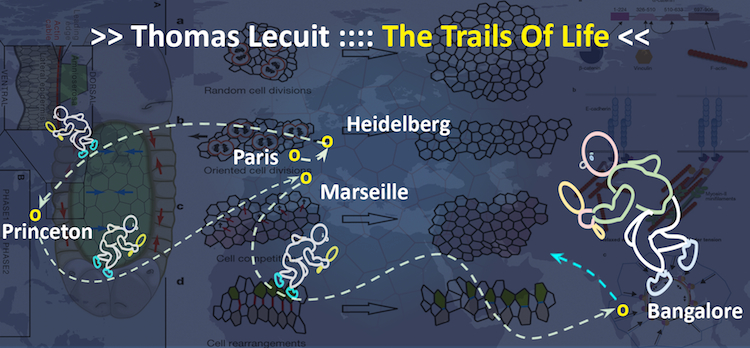

Thomas Lecuit: The trails of life

After spending a year-long sabbatical at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, and just before heading back to Marseille, Thomas Lecuit recently gave his final talk to a packed audience at NCBS. It was full of surprises as the live natural performance of his children occurred in concert with their father's talk, on "Tissue Dynamics".

Here, Thomas Lecuit shares his thoughts about his life-time spent uncovering the secrets of tissue morphogenesis.

Dr Lecuit, how did you become motivated to be a scientist?

When I was a child I was very much fond of animals and plants, and spent a lot of my time as a naturalist, trying to recognize insects, finding out their habitats etc. My grandfather taught me many important things, offered me books or even gave me scientific articles describing new species when I was around 10 years old. That very much showed me the way to combine a natural sense of observation with the effort to organize collections of data. I was very eager to answer many questions from my everyday experience, so I found it normal to investigate by myself. I didn't know that was science, but I was already behaving a bit as a scientist.

As a scientist how do you view this sabbatical and has it brought any transformation in you?

This sabbatical has brought a lot of good exchange, but not so much yet in terms of solid scientific findings. I came here to learn from interactions with the labs of Jitu Mayor and Madan Rao mainly - and I did - and to initiate collaborations. Precise collaborations have emerged that I believe will significantly improve our research on several fronts. It is very exciting to leave NCBS with these new directions in mind. The essence of a collaboration is an opportunity to do together better than each of us alone. I believe this is the situation ahead of us. But it was also good to sit back a bit from my everyday activity, being unable to do some of the usual management work, reducing my traveling load, and thus having more time to discuss and think about the work of my collaborators in Marseille. And also doing some experiments here.

So much can move us away from proper science when we are scientists. It was a good opportunity to focus on the most important things. Also, I had more time to read and think more broadly about what we do, to put it into perspective. Being on sabbatical in a new place, especially in India where things are very different for a European, puts you in a mindset where one is naturally surprised and questioning in his thinking. While this directly affects everyday life, it also affects our intellect and puts you in the mindset of a scientist who should believe in ideas enough to test them experimentally, but who should be ready to drop them and to start anew with no certainty when facing contradictory evidence.

Lastly, NCBS is a place where one meets a lot of people from India and around the world, and also a place of great scientific diversity, which I found very stimulating.

What memories of India, especially NCBS, will you and your family take back?

We have only been here a year and did visit quite a number of places. It is hard to single out one or two memories. I leave with very strong 'impressionist' memories. I will keep with me smells and sounds as much as people we've met and places we've visited, all mixed into an experience of encounter and discovery. The far remote has become familiar. What a great experience for us all!

This country is so contrasted, with so much vitality. It is inspiring to us all, as I often have the impression that, at least in France, we are more concerned with securing our rights than with building our future every day that passes. This is a lesson that we've learned here as well.

We appreciated a lot our life at NCBS. The kids especially had a great time and made a lot of friends with people, our neighbours, and the people who look after the garden, the guards and the drivers. All of them have been part of our everyday life for a year and we will all miss them very much.

What inspired you to become a developmental biologist? In particular, why did you pick Drosophila?

I remember very precisely reading an article in Scientific American about Hox genes and how gene regulation underlies the patterning of the body plan. This was probably in around 1988. I was totally fascinated by this, really amazed that such complex processes could be described in terms of relatively simple gene regulation pathways. I wished then that some day it would be possible to work on things related to this. A few years later, while a student at Ecole Normale Superior in Paris, and having to find a lab for a summer rotation, I was by chance brought into contact with the lab of Claude Desplan, then at Rockefeller University in New York and working on early Drosophila embryonic patterning. That was it! I was sure there was a real opportunity. I remember so well arriving in this fantastic environment. I became totally sure that would be my life: being a researcher and working in a lab. There was enough of intellectual exercise to keep me excited and alive, and enough of experimental work to keep me firmly anchored in reality and humble. The perfect balance.

From your point of view what do you consider as major discoveries that have led developmental biology to new levels?

That we can make sense of so complex processes could seem like a miracle of science but it is a proof of its impressive power.

Looking at the past 50 years of developmental biology, I think there have been two major revolutions. The first one is the progressive realisation that developmental processes are governed by conserved genetic programmes that lay down patterning information from broad fields of cells to single cell identity. The 'gene kit' is quite limited in terms of the number of genes, but of course very complex in terms of its potentiality through the many interactions possible between genes in a network.

The second major revolution is one that we are living now I believe. Namely the fact that developmental biology is amenable to very solid quantitative description and physical understanding. This concerns in particular the mechanics of development from the subcellular to tissue scales where interdisciplinary efforts have completely changed our perspective on how organisms are made and will continue to do so. This also includes the better understanding of how information flows through gene and biochemical networks and how these networks perform complex input/output reactions. It is only the beginning of a new era and it is very fortunate to be part of this with so many colleagues around the world.

How big is your group, and how diverse?

My group is about 12-14 people with a good balance of students and more senior postdocs/research fellows. There is also a good and fruitful combination of geneticists, cell biologists and physicists.

Could you briefly tell us the computational work you do for your research?

We are not doing computational work ourselves but through collaborations. It was first initiated with PF Lenne in Marseille, modelling tissue remodelling with near steady state thermodynamic models. We are using more complex but similar kinds of models to study the interplay between growth and mechanics in collaboration with Hervé Rouault from Paris. This is now done with Ed Munro from University of Chicago; using real time finite element modelling as well as some molecular dynamics based modelling. Finally, I am starting a collaboration with Madan Rao at NCBS using more theoretical analytical studies of cell mechanics.

What kind of challenges and opportunities does Drosophila as a system offer in solving problems related to your research?

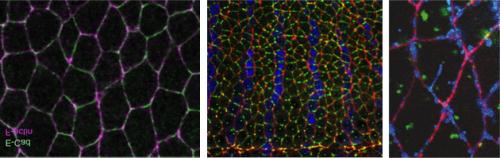

Drosophila is a very powerful system because of the quite unique combination of experimental approaches it offers: from genetics to quantitative imaging at all scales, biochemisty and physical apporaches to probe the micromechanics of cells and tissues.

With the emergence of many model organisms, how do you think they will complement Drosophila research?

I think it will be especially interesting to compare and contrast organisms as live imaging of fluroescent proteins can be done in mice, chicken, fish in addition to flies and worms. We are at a time when some general features/principles are emerging out of these comparisons so we do need many organisms and none of them has any greater intrinsic scientific value according to me. I am just working with the one that I find most powerful given the problems I am interested in.

Techniques like fluorescence imaging have made quantification and real-time observations possible. To what extent have they advanced the field of developmental biology?

Precisely because they allow a rigorous quantitative description at all relevant biological scales from proteins, cellular to tissue dynamics.

Does your research on cell-to-cell adhesion dynamics have direct implications in preventing cancer metastasis?

Solid cancers are complex and involve many steps. Perturbation of cell adhesion and changes in the mechanical properties of cells are part of this. We believe and hope that our efforts to understand the most fundamental basis of epithelial cell mechancis (intercellular adhesion and cell contractility) will shed light on some important steps of cancer progression.

In the long term, where will the current research of Drosophila lead us?

I don't want to know. I want to be surprised. The most exciting is unpredictable.

Research and family: How do you balance them and do you perceive the influence of one on the other?

As many people at NCBS have noticed, my wife and I have 4 children, aged from 12 to 2. This is the source of lots of happiness and my priority in life before science. I do need a strong personal and familial life to find a good overall balance with research. I do not work on week-ends and enjoy holidays with my family because this provides me with the necessary time to rest and think anew on the scientific problems that occupy me all day otherwise. I need a regulate re-booting to be more creative I think. This is just the way I am and everyone is different. It is fortunate I have enough activity at home with my children to make it impossible to work.

Comments

Post new comment